What Are Bonds & How Do They Work?

As a trader, it is critical to understand how bonds work. Bonds are a debt instrument issued by the federal government, municipalities, and corporations. They act as formal contracts to repay borrowed money with interest payments—otherwise known as coupons—at fixed intervals. Bonds issued by the U.S. federal government are called Treasuries. With a tastytrade account, you can seamlessly incorporate bonds in your trading strategy.

What is a Bond?

A bond represents a formal loan agreement where the issuer agrees to pay back the face value of the bond and provide fixed interest payments, or coupons. These coupon payments are paid to the buyer of a bond at fixed intervals, usually once or twice a year. The credit rating and the financial backing of the issuer affect a bond’s price, whereas Treasuries offer lower interest since they are backed by the U.S. government and as such are seen as a lower risk investment. In fact, in financial markets, the risk-free rate is typically tied to the yield on a 3-month Treasury bill, or longer-term Treasury bonds.

What is a Government Bond?

Government bonds are issued by governments to raise funds for spending and other obligations, such as operating the government, infrastructure projects and financing the deficit.

Bonds issued by the United Kingdom are called Gilts, while they are referred to as Bunds in Germany, and in Japan they are called Japanese Government Bonds, or JGBs. In the United States, government bonds are called Treasuries. Treasuries form the cornerstone of the bond market, highlighted by exceptional daily volume and liquidity. They are bought and sold not only by individual traders but by financial firms, banks, local governments, pension funds, and foreign countries.

They are generally considered one of the safe investments, and as such, are used by traders to reduce volatility in their portfolios.

The U.S. Department of the Treasury issues new Treasuries through auctions. These auctions are held at regular intervals and are announced ahead of schedule to give investors and financial firms the opportunity to bid on them in the primary market. The duration and amount of bond auctions are determined by borrowing needs of the U.S. federal government.

After bonds are issued onto the primary market they then start to trade in the secondary market where they can be bought or sold. Prices for bonds in the secondary market are influenced by factors such as interest rates, the economy, and market demand. The secondary market consists of over-the-counter (OTC) trading that involves the direct buying and selling of bonds between individual participants.

Traders can also participate in speculating on Treasury prices via the futures market. Treasury bond futures have traded on the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) since 1977. Treasury futures include 2-year Treasury Note futures (/ZT), 5-year Treasury Note futures (/ZF), 10-year Treasury Note futures (/ZN), 30-year Treasury Bond futures (/ZB), and Ultra Treasury Bond futures (/UB). These products are utilized by investment firms and individual traders to speculate on prices and to hedge against portfolio volatility. These products also include options on futures, which enhances the ability to structure trades.

Options on bond futures are derivatives that give investors the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell bond futures at a certain price by a future date. These options on bond futures allow traders to gain additional flexibility and leverage to speculate and/or hedge against interest rate expectations. The 10-year T-Note futures contract (/ZN) is a popular Treasury future among options traders.

What is a Corporate Bond?

Corporate bonds are debt instruments issued by a company or firm. In addition to equity, corporations raise capital through selling bonds. However, corporate bonds generally come with more risk, as companies can and do default.

A default occurs when a company can no longer honor its financial obligations. When that happens, it can result in bond holders not receiving their capital back. Because of the additional risk, corporate bonds have to offer higher interest rates to incentivize buyers who would otherwise seek safer debt like government bonds.

Corporations issue their bonds in the primary market with a bond offering. These offerings are typically facilitated by financial firms like investment banks. Institutional investors buy these during the bond offering and include mutual funds, hedge funds, pension funds, insurance companies and banks.

Corporate bonds go on to trade in the secondary market to allow issuers and investors to buy and sell these bonds before maturity. The secondary bond market is primarily conducted over the counter, but products like exchange-traded funds (ETFs) trade on exchanges. These ETFs represent a bundle of corporate bonds and allow for a liquid market where they can be bought and sold by investors.

Investment grade and high yield, sometimes referred to as junk bonds, are the two categories that separate corporate bonds. These classifications are based on the issuer’s credit quality, primarily based on the company’s financial stability and ability to meet its financial obligations. Investment grade bonds are less likely to default because they have a higher credit quality. However, they offer lower yields than their high-yield peers, which come with a lower credit quality. Because junk bonds have a lower credit quality, they have to offer higher yields to attract buyers for their debt.

What is a Municipal Bond?

Municipal bonds, or munis, are debt securities issued by governments that include states, cities, counties and other types of government entities below the federal level. The capital raised from this debt are typically used to fund public projects, schools, hospitals and roads.

Compared to corporate bonds, municipal bonds have a lower risk of default. This is because the governmental entities issuing the bonds tend to be conservative with spending and have a projected tax base that reduces the risk of default.

Many municipal bonds come with a call provision. This means that the issuer—the governmental entity—can call a bond, which results in the investor losing future interest payments while receiving the face value of the bond back before the maturity date. Bonds are typically called when interest rates drop.

What is an Agency Bond?

Agency bonds are like Treasuries, but instead of being issued by the Department of the Treasury they are issued by individual government agencies, or government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs).

Agency bonds offer higher yields than Treasuries but lower yields than corporate bonds and even most municipal bonds. This is because they are not explicitly backed by the full faith and credit of the United States government. However, agency bonds still hold high credit ratings like that of the U.S. government itself.

The Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA), or Fannie Mae, is one example of a GSE that issues agency bonds. During the 2008 financial crisis, the yield on these agency bonds rose as investors feared that the mortgage crisis would pose a default risk for FNMA. Fannie Mae never defaulted, but the event highlights how investors see agency bonds when default risks arise.

How Do Bonds Work?

Bonds are a fixed-income investment representing a debt obligation where the issuer agrees to lend money for a certain amount of time at a fixed interest rate. They are bought and sold not only by individual traders but by financial firms, banks, local governments, pension funds, and foreign countries. When an individual buys a bond, they act as the lender, and the entity issuing the loan is the creditor.

How Do Bonds Generate Income for Investors?

Bonds generate income through a fixed interest rate payable to the buyer. These are referred to as coupon payments. Coupons are a reliable source of income that is known at the time of purchase, which is one of the primary reasons that make bonds an attractive investment. Treasuries, for example, pay out these coupons semiannually, or twice a year. A 5-year Treasury note with a 2% annual yield will generate $20 per year to the investor, or $100 over the course of the note’s life.

Bond Example | |

|---|---|

Principal | $1,000 |

Annual coupon | $20 ($1,000 x 2%) |

Total coupons over the life of the bond | $100 ($20 x 5 years) |

Characteristics of Bonds

Maturity

Maturity refers to the length of time until the bond matures, at which time the principal, or face value, is paid back to the buyer. For instance, a 10-year Treasury bond will mature 10 years from the date it was first issued. Another term in bond trading is the term to maturity. The term to maturity refers to the remaining time until the maturity date is reached. For instance, if the date is January 1, 2026, and the 10-year note matures on January 1, 2027, then the term to maturity is one year.

Put simply, maturity refers to the date that a bond will stop trading, whereas term to maturity represents the time left until a bond will stop trading. A bond with a longer maturity date, such as a 30-year Treasury bond, will typically pay more interest than a 5-year Treasury Note, since an investor's money will be tied up for a longer amount of time, thus requiring a higher interest payment to attract buyers.

Credit Rating (Quality)

Understanding the credit rating of a bond is crucial for trading them. Treasuries typically have the highest credit rating and are perceived as one of the safest instruments to invest in because they are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. However, corporate bonds are seen as riskier, and that risk is highly dependent upon the credit rating of the issuer. A company with a weaker balance sheet will almost always have to offer a higher yield to compensate investors for the additional risk.

This risk primarily manifests itself through the threat of default—that is when a company can no longer service its debt and other obligations. Bonds with very high yields are often referred to as junk bonds. These types of bonds can offer yields of 10% or more, but they come with the risk that the company will default. A company that defaults is unlikely to be able to pay back investors, meaning that it is possible that the bond won’t reach maturity and pay back its face value to the investor.

Credit rating firms are a vital part of the bond market and issue ratings to bonds based on their risk of default. Firms such as S&P Global, Moody’s, and Fitch are some of the firms that issue credit ratings on bonds. Each firm has its methodology to rate bonds, but the below is a general breakdown of the rating and the associated risk to the bonds being rated:

- AAA: Highest credit quality and considered the safest

- AA: Very high quality with slight susceptibility to changes

- A: Strong, with some sensitivity to economic shifts

- BBB: Lowest investment grade; adequate but more sensitive to conditions

- BB: Speculative; higher risk of default but less vulnerable immediately

- B: Highly speculative; significant risk of default

- CCC: High risk, vulnerable to adverse conditions

- CC: Extreme risk, with payment difficulties expected

- C: Near default; financial distress underway

- D: Default; failing to meet obligations

Face Value and Issue Price

Face value, or par value, is the amount that the issuer agrees to repay at the time of maturity. This is a vital component in determining interest payments throughout the life of the bond. The market price of the bond can fluctuate in the secondary market due to changes in interest rate expectations and/or the credit rating of the issuer. Overall market conditions can also impact the market value of a bond. The price changes due to these factors are what causes bond prices to shift and presents traders with an opportunity to speculate on the price of bonds.

Current Yield and Yield to Maturity

Perhaps more important for trading bonds is the current yield and yield to maturity (YTM). The current yield looks at the bond’s interest payments relative to its market price, which provides a timely view of its return. The yield to maturity accounts for the remaining interest payments, whether made annually or more frequently, in addition to potential gains or losses assuming the bond is held to maturity. The YTM is expressed as an annual rate, providing a figure that represents the total expected return of the bond if held to maturity.

Coupon Rate

The coupon rate is the fixed annual interest payment that is due to the bondholder by the issuer. It is expressed as a percentage of the face value of the bond. The coupon rate is important for a bond when issued in the primary market when investors assess the attractiveness of the interest payments at issue.

Why Do People Buy and Invest in Bonds?

Investors like bonds due to their ability to deliver consistent income that is known at the time of purchase. They also provide a promise, but not a guarantee, that you will receive the face value of the bond back at its maturity. Bonds give investors the opportunity to diversify their portfolios away from equities, which are generally seen as a riskier investment. However, because they trade on an open market, investors can also speculate on bonds with the goal of capital appreciation.

Interest Rates and Monetary Policy

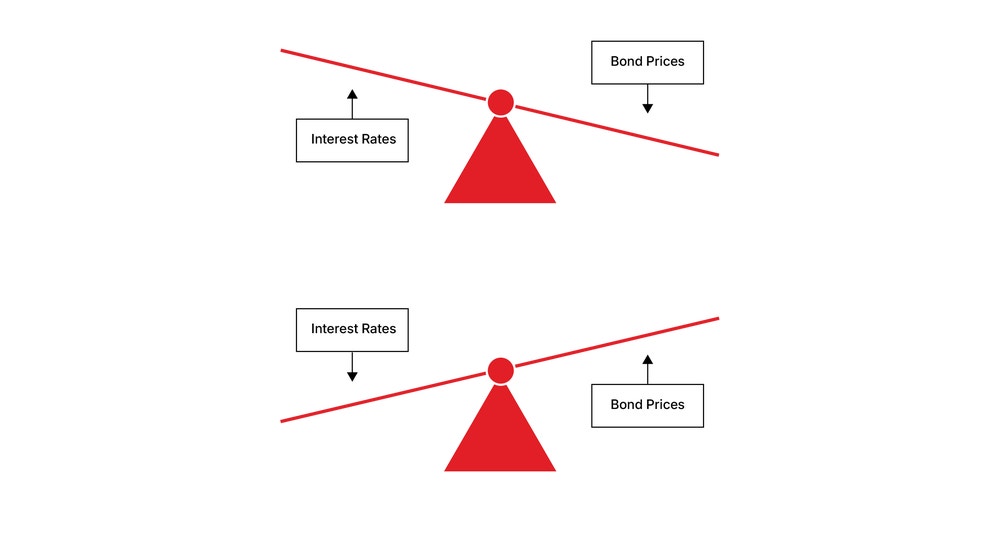

Treasuries, and to a less extent other bonds, are sensitive to interest rate changes. This is because bonds offer a fixed coupon payment. When interest rates rise, or are expected to rise, newly issued bonds will offer higher yields to attract investors. Because of this, bonds that are trading in the secondary market will fall in price, as the new bonds offered in the primary market offer higher yields.

The Federal Reserve, or the Fed, is the U.S. monetary authority. When the Fed increases interest rates, Treasury prices typically will fall. This is due to opportunity costs and market adjustment factors. When investors can find better returns in the newly issued Treasuries that offer higher yields, it makes older bonds with lower yields less desirable, representing the opportunity cost adjustment. Existing Treasuries fall when interest rates rise because the effective yield, or current yield, needs to align with the prevailing interest rate, representing the market adjustment factor.

Bond Examples

Government Bond Example

Say it is January 1, 2025, and you want to buy $1,000 worth of Treasury Notes that pay a coupon rate of 3%. The interest received per year, in semi-annual coupon payments, would be $30 (1,000 X (3%/2) = 1,000 X 1.5% = $15). You will receive $300 over the life of the note ($30 X 10 = $300). Upon the maturity date of January 1, 2035, you would receive the final interest payment in addition to the return of the face value of the note ($1,000). Your total return from the investment would equal the face value plus the interest payments received over the life of the note ($1,000 FV + $300 coupon payments).

Corporate Bond Example

Say it is January 1, 2025, and you decide to buy $1,000 worth of corporate bonds issued by Willy Wonka Corporation, which pay a coupon rate of 10%. The bond holds a B rating by a major rating agency, indicating a higher risk of default compared to higher-rated bonds, such as A’s or triple B’s. This B rating suggests that while the bond pays a high interest rate of 10%, there is a significant default risk associated with the issuing company’s financial stability. The interest received per year, in semi-annual coupon payments, would amount to $100. Remember, corporate bonds generally pay more interest than Treasuries to account for the higher risk of default. Upon the maturity date of January 1, 2035, you would receive the final interest payment of $50 plus the return of the face value of the bond $1,000. Your total return from the face value repayment and the interest over the life of the bond would equal $2,000 ($1,000 FV + $1,000 coupon payments).

FAQs

Bonds generate income through interest and principal repayment, with market pricing influenced by interest rates and credit quality.

Income from bonds comes from coupons and is augmented by capital gains from market price changes.

Bonds can offer stability and diversification, often complementing equity positions. Investors appreciate their potential for risk-adjusted returns.

Government T-notes represent a solid example of risk-balanced investments, with regular interest payments.

Yes, a bond is a formal loan agreement between the issuer and buyer.

Bonds typically offer more stability than stocks but at lower return potentials, often serving as a defensive portfolio component.

All investments involve risk of loss. Please carefully consider the risks associated with your investments and if such trading is suitable for you before deciding to trade certain products or strategies. You are solely responsible for making your investment and trading decisions and for evaluating the risks associated with your investments.