What Are Futures and How Does Futures Trading Work?

Futures are derivative contracts that give you the obligation to exchange an asset at an agreed-upon price by a predetermined date. It is trading the future price of a given asset.

What Are Futures?

Futures are standardized contracts that represent an agreement between two parties, a buyer and a seller, to trade a particular asset at a set price before a certain expiration date, called the expiry. Regardless of what the underlying asset’s market price is at the time of the exchange, the price will remain fixed as per the contract.

Assets that can be traded in this way include baskets of company stocks, commodities, interest rates, cryptocurrency, and currencies. The quantity of the underlying will be specified in the futures contract.

Sign and sealed but rarely delivered. Whatever the quantity, you probably won’t need to clear up your basement. Futures are financial derivatives that enable you to speculate on the price of an asset without ever owning it. Only a tiny percentage of futures contracts end in physical delivery as most positions are closed before expiration.

In cases of physically deliverable futures, a ‘first notice date’ applies. This date refers to the first day a delivery of an underlying asset can be made. To avoid delivery, tastytrade sends a first notice date email a few days before the actual day, detailing when the contract can be closed or rolled into the next cycle. Agriculture, metals, and interest rates futures contracts are subject to first notice; while the same three plus currency and energy (excluding E-mini) can be physically delivered.1

How Do Futures Work?

Futures work by locking in the current market price and setting it as the fixed price at which an underlying asset will be exchanged later. At the future date – on or before the expiration of the contract—the market price will more than likely be different. The agreed-upon price would then be either higher or lower than the new market price.

If the new market price is higher than the futures contract price, the buyer benefits as they will pay less for the underlying asset. Conversely, if the new market price is lower than in the agreement, the seller benefits because they will be paid more than the current price per quantity of the asset. Of course, where one party benefits, the other loses out.

There are three main types of future traders:

- Speculators take a position on the direction of an asset’s price movement. Most retail traders fall under this future trader type

- Producers (hedgers) aim to limit their risk by locking in prices of expected production (goods they manufacture such as oil, gold, and wheat)

- Position holders keep their trades open for an extended period (could be anything between weeks and years)

The definition and workings of futures fly in the face of a popular assumption that it is all about predicting what is to come on the financial markets. As nice as that would be, you are still speculating on upcoming price movements and there’s potential for profit if all goes well.

Buying vs. Selling Futures

The basic notion of buying and then selling is a widely known concept in the world of trading. On the back of this, you can buy futures contracts (or go long on them) with hopes that the underlying asset it covers appreciates, so that you can sell it at a higher price to make a profit.

However, you can also sell futures contracts if you think the underlying asset will depreciate – also known as going short. You would then buy it back (or cover it) at a lower price to earn a profit.

A common question among those new to the concept of shorting is, ‘how can you sell something you do not own?’ When you are the seller of a futures contract, you agree to sell the underlying asset at a later date, at the futures contract price.

In summary, when going long, you hope to profit by selling the asset at a higher price. You would close a long position to sell it. Conversely, you hope to profit by closing your short position at a lower price when going short. To close a short position, you must buy (or cover) it.

Futures Contracts Standardization

Liquidity is ensured in futures contracts through standardization—setting a precise benchmark on a variety of factors based on the underlying asset. This is done by outlining specifications such as:

- The underlying asset: the exact asset, e.g., basket of stocks, commodities

- Settlement type: cash settlement or physical delivery

- Contract unit: the quantity of the underlying asset covered in one contract, e.g., 1,000 barrels of crude oil

- Currency: the currency of the futures contract’s price quotation

- Quality: the grade of the underlying asset

- Date of delivery: when the final cash settlement, or the delivery, will be made

- Last trading date: the day before the expiry date of the contract

- Tick size and value: the increments by which prices can fluctuate and its worth, e.g., the tick size for crude oil is 0.01 and the tick value is $10

- Maximum price fluctuation permitted: price limit that is allowed within a trading session

Mark-To-Market in Futures

Futures and futures options are marked-to-market on a daily basis according to the trading day’s settlement price. Therefore, the IRS refers to these as Section 1256 products.

Mark-to-market is a finance term, so it's not exclusive to futures trading. With regards to futures contracts, marking-to-market is a procedure of valuing assets at the end of each trading day, when profits and losses are settled between long and short positions.

This way of measuring fair value according to market price means that, with the change in value of the contract each day, a settlement will be made to reflect this.

Let us put this into context.

Mark-To-Market in Futures Trading Example

Since a buyer is bullish and a seller is bearish, a lower price at the end of the day would mean a loss for the long position and a gain for the short position. The buyer and seller’s accounts are updated daily (cumulative gain or loss) based on this until the expiration, or when the position is closed.

The change in value from the futures price, as well as the direction, determines gains and losses. The party with the position that matches direction of the change in value will collect the difference in value (from the futures price) at the end of each day, while the other makes a loss equivalent to the change in value. However, unrealized losses will only be factored in once the position has been closed.

Find out how futures settlement can affect your taxes

Notional Value and Leverage

Notional value is the total worth of the underlying asset that is controlled in a derivatives trade, i.e., the amount you stand to lose. It does not include additional fees such as commission and margin relief.

Buying power can fluctuate based on the position and market volatility. That is why you do not only need your initial margin amount, which is used to open your futures position, but you also need maintenance margin. This is the minimum amount needed in your account at any given time. A margin call occurs if the amount in your account is less than the maintenance margin.

Notional value is calculated by multiplying the spot price with the futures contract size, or number of units of the underlying asset. Let us continue with our example of a 1,000 crude oil barrel futures contract at a price of $75.72 per barrel ($75.72 x 1,000). The notional value at risk in this case is $75,720.00.

Market value differs from the notional value. It is the spot price of the underlying asset per unit, or the futures contract price. As per the example, the market value of crude oil is $75.72.

Further, leverage has a significant impact on your trading. It means that you must only commit a certain percentage of the full value of the trade upfront. Despite putting forth less initially, your risk remains the same for long positions—the notional value. If you went short on a futures contract, however, your risk is not capped.

Futures Contract Tick Size

In derivatives trading, a contract’s tick size is the smallest increment by which prices of the underlying asset can fluctuate. An exchange sets the tick size for an instrument. On the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME), the tick size for crude oil is 0.01 and each point is worth $1,000. Multiplying these two values gives you the tick value—which, in this case is $10 (ticks to a point). Points are on the left side of the decimal point of a price and ticks are on the right.

If the price of crude oil moves up 25 ticks (0.01 x 25) from the spot price in the example ($75.72), it would then become $75.97. That might seem insignificant—but multiplied by the tick size ($10), it accounts for a $250 change in your profit or loss.

This means you stand to gain $250 if you went long or lose $250 if you took a short position. If you took a position on multiple futures contracts, you would multiply this value by the number of contracts.

Futures Contract Example

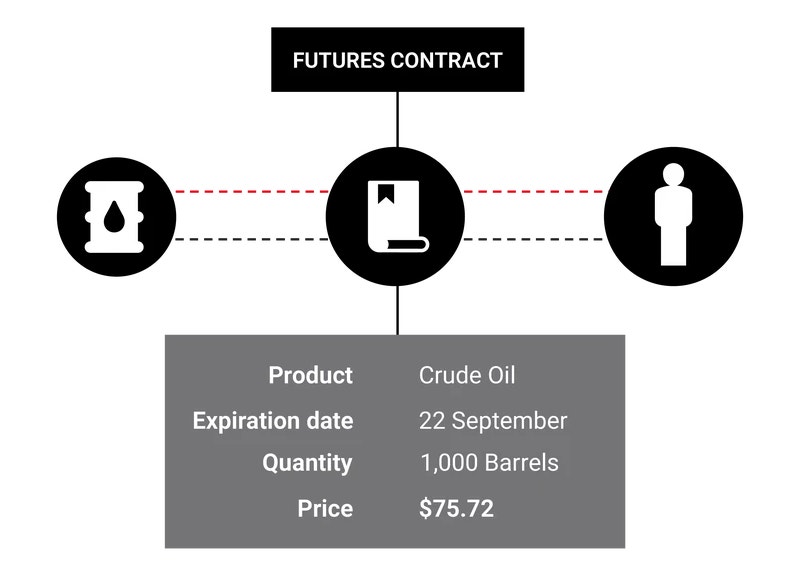

A futures contract includes some key information as outlined in the example below. This includes:

- Product: the type of underlying asset, e.g., crude oil is a commodity

- Expiration: the day on which the contract ends

- Quantity: contract unit, e.g., 1,000

- Price: the agreed-upon price of the futures contract

Futures Trading Example

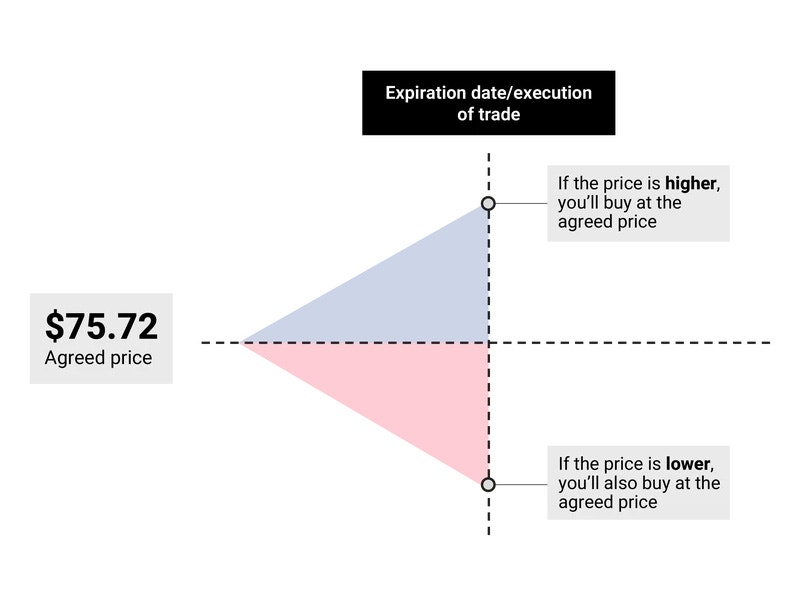

Futures trading spans from the time the contract is entered (also known as ‘opened’) to the time the position is exited (also known as ‘closed’), or when this happens by default at expiration. If the market price is higher when the exchange is made, you would benefit if you took a long position (buying), and the seller would lose out.

On the other hand, when the market price is lower than the futures contract's predetermined set price, that would benefit the seller, and the buyer would lose out.

Suppose you buy a crude oil futures contract, and you have agreed to purchase 1,000 barrels of it at a price of $75.72 by September 22nd.

If the crude oil price drops and stays low after you enter the agreement, you will incur a loss if this is still the case at expiration. But if it rises and stays above the futures price, you will make a profit.

Either way, you still have a chance to try to lock in profits or limit losses before the expiry date. If the market moves against your position, you can open and close it anytime. There are no pattern day trading (PDT) rules for futures, as they are not securities. This is useful when you want to change your directional assumption in a particular futures product.

Futures Options: What Are They and How Do They Work?

Unlike their equity option counterpart, which is tied to 100 shares of stock, futures options are options that are tied to a single futures contract. It is a derivative of a derivative. Similarly, the value of the option adheres to each futures contract tick value.

Like their equity option counterpart, buyers of options on futures give the right to buy or sell the underlying futures contract at the strike; and sellers of options on futures have the obligation to buy or sell the underlying future at the strike price.

Details that are typically included in an option on a futures contract are the product, the future’s contract month, and the set price to buy or sell the futures contract.

Why Do Futures Exist? A Brief Intro to Risk Management

Agricultural commodities such as corn, wheat, and soybeans are usually the first things that come to mind when a new investor thinks about a futures contract. One reason for the development of futures was for farmers to manage risk and reduce uncertainty—also known as risk management.

In business, there are price makers and price takers. Price makers can set what they will charge for a product or service. Normally this is the case when a company is selling something unique, without a competitor. Price takers must buy or sell something at a price that is determined by a broader market of other transactions because their product is not unique and has competitors.

As an example, farmers are price takers since the market determines the price they receive. Farmers have a unique business model because they will not know what the market price of their crop will be until it is ready to be sold. Since the market determines the price farmers can receive for their crop, they cannot be a price maker. The same risk applies to other commodity producers since it takes time for other commodities like wheat, gold, oil, or livestock to grow, mine, drill, or be ready for market.

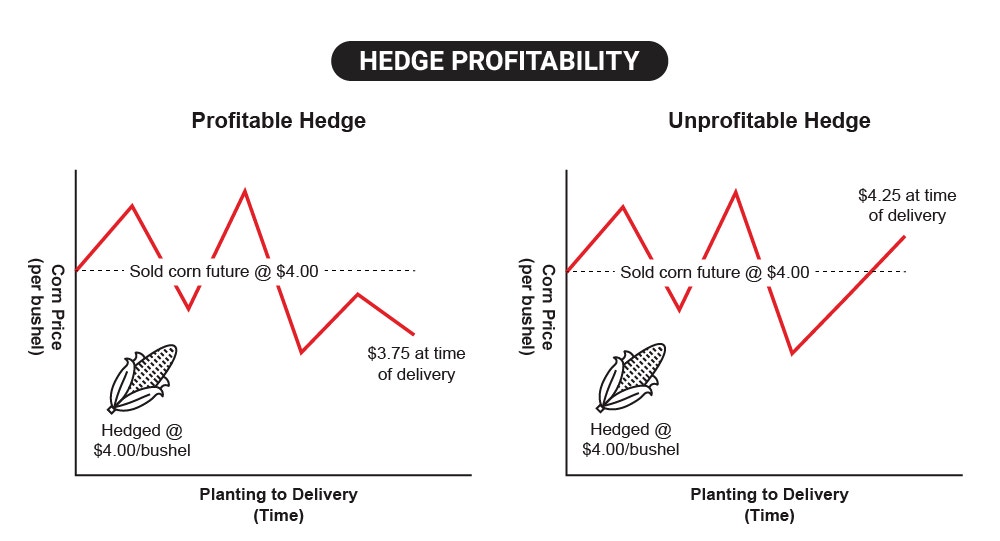

Using the example of a farmer, the market price of corn at the time of planting may be $4 a bushel. At the time of harvest, it could have decreased to $3.75 a bushel. Sure $0.25 may seem like a small amount, but farmers usually sell thousands of bushels of corn at harvest. A $0.25 difference over thousands of bushels could be the deciding factor for a profitable harvest.

Futures allow farmers and other producers to mitigate the risk of falling prices and price uncertainty upon delivery. By selling a futures contract, they can lock in a selling price for their crops to be delivered at a future date. This notion of locking in a price for a future delivery date is where futures get their name. We illustrate this in The Role of a Hedger section later on.

Additionally, futures also allow consumers of a commodity to lock in the purchase price for delivery at a future date. Continuing the corn farmer's example, a cereal maker that produces cornflakes with concerns about rising corn prices in the future can lock in the price of corn by buying a futures contract for delivery at a future date.

Overall, futures are designed to help producers and consumers manage risk surrounding price uncertainty. However, you do not have to be a farmer, a commodity producer, or a manufacturer to use futures contracts to manage and mitigate risk.

The Role of a Hedger

There are two types of hedgers in the futures market: bona fide hedgers and hedgers.

Bona fide hedgers are commodity producers and consumers. Producers include wheat farmers or oil drillers who use futures to lock in a sale price and intend to deliver the commodity to a buyer of the respective futures contract. Buyers of futures contracts include consumers or manufacturers who use a commodity as a business input, like a cereal maker or oil refiner.

Producers may use futures to lock in a sale price when they are concerned about falling prices of the commodity they produce at the time of delivery. Conversely, consumers may use them to lock in a future purchase price if they are concerned about rising prices. Futures help stabilize forecasting future profits and losses by locking in prices.

Although a producer could lock in a price early to offset price uncertainty, it is not without risks. At the time of delivery, the commodity could be trading at a much higher spot price, and since a futures contract is binding, the producer could end up selling at a much lower price than they would have if they had not hedged.

However, if the spot price is lower at delivery, the producer benefits by having locked in a higher sale price.

The table below illustrates how hedging can help offset price uncertainty for producers, using a corn farmer as an example. Although some hedging could be unfavorable at the time of delivery, when bona fide hedgers sell futures, they eliminate price uncertainty at the time of delivery.

Examples of bona fide hedgers using futures include:

- Farmers hedge against crops like corn, wheat, and soybeans

- Ranchers hedge against livestock

- Miners hedge against precious metals, like gold or silver, and copper

- Drillers hedge against crude oil or natural gas

It is important to note that tastytrade does not support bona fide hedging futures accounts since we do not support physical delivery.

You do not have to be a farmer, miner, oil driller, or other commodity producer to use futures as a hedging tool. For example, investors seeking protection against a portfolio of long stocks can use equity index futures to help offset or potentially reduce losses.

Investors using futures to safeguard a portfolio are typically large investors or institutional investors like a pension fund due to the sizeable notional value of each futures contract. Investors who use futures to protect a portfolio of treasuries or stocks may use interest rate futures or equity index futures as hedging vehicles. Banks or financial institutions looking to manage their currency risk or overnight lending rates may also turn to currency or Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) futures.

Investors at tastytrade can also use futures as a hedge to protect their portfolio. However, investors will want to consider their portfolio's size when determining which contract size to use, such as an E-mini or E-micro futures contract. Please visit the tastytrade Help Center to view a complete list of available futures contracts for trading at tastytrade.

Overall, bona fide hedgers and hedgers trade futures to reduce or offset risk and are known as risk makers.

The Role of a Speculator

Unlike hedgers, who use futures to protect their investments or business interests, speculators have no intention of delivering or taking delivery of the underlying asset.

For example, a speculator can take a long or short position on corn, gold, natural gas, or any other physically delivered futures contract without any intention to deliver or take delivery of the commodity. Instead, speculators only aim to profit from trading the contract.

Long Futures

- Assumption: Rising prices

- Opening trade: Buy to open

- Closing trade: Sell to close

- Profits occur: Sell or close the contract above the purchase price

- Losses occur: Sell or close the contract below the purchase price

Short Futures

- Assumption: Falling prices

- Opening trade: Sell to open

- Closing trade: Buy to close

- Profits occur: Cover or close the contract below the sale price

- Losses occur: Cover or close the contract above the sale price

Speculators play a vital role in the futures marketplace by providing liquidity and price stability. Like any other market, liquidity increases as the number of market participants increases, leading to more price stability. As a result of speculators, prices can go up or down to reflect current events or market conditions and provide a more accurate market price for a specific asset. Investors could benefit from rising or falling prices by taking a long or short position bias on a futures contract.

The tastytrade trading platform empowers investors who wish to speculate in futures with a wide array of trading tools and features, such as a wide range of charting tools to locate an opportunity and multiple trading interfaces based on your trading style.

Futures traders can put their ideas to work and execute trades using the Active Trader Interface, which provides a visually intuitive interface to enter, adjust, and manage trades rapidly. The Grid Mode also allows investors to combine technical analysis with trade entry by allowing traders to place trades on a chart. The tastytrade trading platform also has built-in watchlists listing all available futures contracts, including micro-sized contracts. Please visit the tastytrade Help Center to learn more!

How To Start Trading Futures

- Do your research to get an understanding of how futures trading works

- Create an account or log in

- Choose your preferred market and asset

- Create a trading plan and manage your risk

- Open your futures position and monitor it

- Close your position if you want to do so before the contract expires1

Ready to Conquer the Futures Market?

FAQs

In any type of trading activity, risk is a factor and should be given consideration. That is why it is important to build a rock-solid foundation of knowledge on all the moving parts in futures trading, e.g., the impacts of leverage, before getting started so that you can manage your risk accordingly.

You can buy stock index futures with tastytrade by following our steps on how to trade futures.

Some differences between futures and stocks include:

Futures:

- Financial derivative contracts that allow you to trade the future price of unique sectors and products

- Obligation to buy or sell in the future at a predetermined price

- The exchange must happen on or before the contract expiration

- Less risk of insider trading

- Not subject to PDT rules since futures aren’t securities (requires a margin account)

Stocks:

- Financial instruments that allow you to take partial ownership in your favorite companies or ETFs

- Can buy and sell (with no obligation) at whatever the market price is

- No time limit—can take your position in 10 years or not at all

- A single stock is prone to leaking of information Subject to PDT rules, as stocks are securities

The question of which is better between futures and options has no particular correct answer. It depends on how you want to get exposure, what your risk appetite is, and the trading time horizon. Upon doing a deep dive on both futures and options, you’d be better poised to make a decision based on your needs.

With tastytrade, there’s no minimum account balance to trade CME futures in a margin account.

But if you’re trading in an IRA, start-of-day net liquidation must be $25,000 for standard CME futures contracts and futures options and $5,000 for CME micro E-mini futures and CME options on micro E-mini futures. Whichever account you use, you need to ensure that overnight requirements are met.

1 tastytrade does not allow for delivery of physically delivered futures. Financially settled futures can be held to expiration, but not anything that has a deliverable.

Futures and futures options trading is speculative and is not suitable for all investors. Please read the Futures & Exchange-Traded Options Risk Disclosure Statement prior to trading futures products.

All investments involve risk of loss. Please carefully consider the risks associated with your investments and if such trading is suitable for you before deciding to trade certain products or strategies. You are solely responsible for making your investment and trading decisions and for evaluating the risks associated with your investments.